The Economic and Social Origins of Cyberpunk

February 27, 2021 | 25 min. read

Dark Dreams

The year is 20XX. You are a denizen of a megalopolis: a sprawling, squalid, concrete mass lived in by tens of millions of people. Most of the Earth's population has been urbanized and lives in similar conditions - it's likely you've never seen wild plants or animals outside of a zoo or very old documentary. Skyscraping spires of glass and steel pierce the sky for miles around, casting shadows in the few places below not constantly illuminated by neon streetsigns. The air is thick and hazy, and it's overcast more often than not; whether from pollution, ecological disaster, chemical warfare, or all of the above, even the atmosphere itself is hostile and alien to the human body. The rest of the city is just as inhuman or unfamiliar. Autonomous vehicles dominate the streets, and even the vending machines cry out in human voices to persuade passersby to spend a buck and consume their contents. Half the streetsigns are illegible to you, written in the language of one of the many foreign diasporas now large enough to outnumber the city's native populace. None of this is too surprising, though, considering the political circumstances.

It's a notion of a bygone era to consider the city the jurisdiction of a particular people or nation-state (or any government in particular, for that matter). The dominant rulers here are the megacorporations. Everywhere the eye can see is plastered with insipid advertisements, reminiscent of how countries once planted flags to claim territory. Despite their omnipotence and opulence, the majority of the population working for the megacorps are the definition of wage slaves. You make enough to rent a shoebox apartment (you likely rent rather than own most of your possessions, in fact) and some trivial comforts - your only real escapes are shallow worldly pleasures or consumption of digital media. Wealth inequality is astronomical, and so are the crime rates; the only real way to get ahead is through less than legal means. Hacking, drug dealing, prostitution, and any manner of leg-breaking are some of the more pedestrian trades. What's left of the city's institutions are simply stretched too thin or too starved of resources to really deter or prevent crime. What most street urchins truly fear is disrupting the delicate machinations of a megacorp or crime lord. The distinction between the two is in some cases hazy, and in more cases nonexistant.

The world in general seems like it's been living on borrowed time for some while now. Humanity has never been further from what you feel it was meant to be, and every aspect of society has been accelerated or twisted into a cruel mockery of what was once good and pure. Whether it's climate change or rogue AI or some other cataclysm, the end of it all seems more and more likely with each passing year. But there's never a bang, only more whimpering.

Or at least that's what life would be like if you lived in a cyberpunk dystopia. Thankfully, you don't.

...right?

Architectural Aesthetics

Cyberpunk is somewhat difficult to pin down. Some argue that it's a distinct subgenre of science fiction with specific narrative requirements, while other say that it's more a common aesthetic than a genre per se. Frankly I think the distinction is pedantic and not really useful for any kind of literary analysis, so I'll just use the same criteria the Supreme Court used to distinguish pornography from art featuring nudity - I know it when I see it.

Most stories considered cyberpunk contain all the elements illustrated in the vignette above - advanced technology, megacities, foreign influence, crime, accelerated capitalism, etc. Perhaps the urtext of cyberpunk is William Gibson's 1984 masterpiece Neuromancer. This book basically ticks all the boxes and is the metric that all other prospective works of the genre/aesthetic are measured against. A few years previous in 1982 saw Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, which doesn't involve hackers or the Internet but does feature near-future megacities, a megacorporation playing the part of Goliath, and neon signs in Japanese. Another cyberpunk-adjacent work is Ridley Scott's Alien (1979). Set not on Earth but rather a space freighter contracted by a massive and morally ambiguous conglomerate known as Weyland-Yutani (or more ominously referred to by the characters of the film, simply "the company"), there are still themes of technology and corporatism run amok.

These are just the first few identifiable cyberpunk works, but there are obviously a lot more popular or archetypal examples. Especially in Japanese media, like the anime Akira or Serial Experiments Lain, is cyberpunk practically perfected. As video games matured as an art form, there were also some great cyberpunk games like Deus Ex, System Shock, and the Shin Megami Tensei series. You could perhaps point to EDM or dubstep being cyberpunk (in that they're significantly influenced by technology, and their association with rave culture) but this feels a little out of place - in my personal opinion, cyberpunk is primarily a label for visual and literary media.

There's a pattern here, however. Take a closer look at the first few "cyberpunk" movies listed above. What do they have in common? Well, they're all American movies made in the late 70s to mid 80s. It's kind of odd for such a specific and well-established genre/aesthetic to appear in such a flash, yet also be so culturally antifragile. I can think of golden-age sci-fi with its flying saucers and little green men or the superhero blockbusters of the 2010s as similarly explosive genres, but both have (thankfully) come and gone. What about cyberpunk has made it stick?

Let's digress for a moment. I'd call it

This is a very hand-wavey, dogmatic, and probably baseless claim. It seems like people love to take hand-wavey, dogmatic, and baseless claims and turn them into axioms, though. Unrelated, of course, but I personally believe a good name for the principle explained here would be Snelson's Law.

that it takes a good five to ten years between a real-life event to occur and for real art influenced by said event to come to fruition. Make a movie about a tragedy while the dust is still settling, and you're a Hollywood schmuck making a quick buck off of someone's suffering. Make a movie too late, and it's just not really interesting or relatable to people (unless it's an evergreen topic or of great importance to national identity, like WWII or The Wild West) and therefore probably won't become commercially successful or artistically influential.

So, let's assume this general rule holds true. Cyberpunk was born in the US in the late 70s and early 80s, so it must have been influenced by the events of the early to mid 70s. The images in my mind of that era, though, are things like the the Beatles, Vietnam, and mid-century modern furniture. I certainly don't think of megacorporations or neon Japanese signs or computer hackers. How could reality possibly influence this sort of fiction?

Brave New World

One of the most important (and to most, unknown) diplomatic treaties ever written is the Bretton Woods Financial System. You can read the full text and history behind it, but the main gist of it is rather simple: post-WWII, the US, Canada, most of Western Europe, and Japan all signed an agreement to peg their respective currencies to the gold standard and maintain close exchange rates. This system was in place until 1971 when (for reasons outside the scope of this blog post) President Richard Nixon withdrew the US from the Bretton Woods agreement and the system as a whole collapsed. This essentially turned the dollar into the free floating fiat currency and near-universal tender that we all know it as today. It also made the world as we knew it, to put things lightly, go absolutely fucking bonkers.

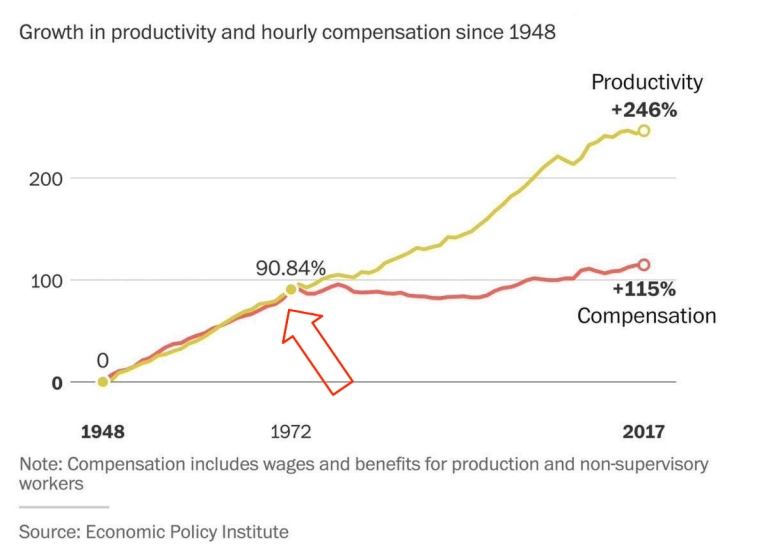

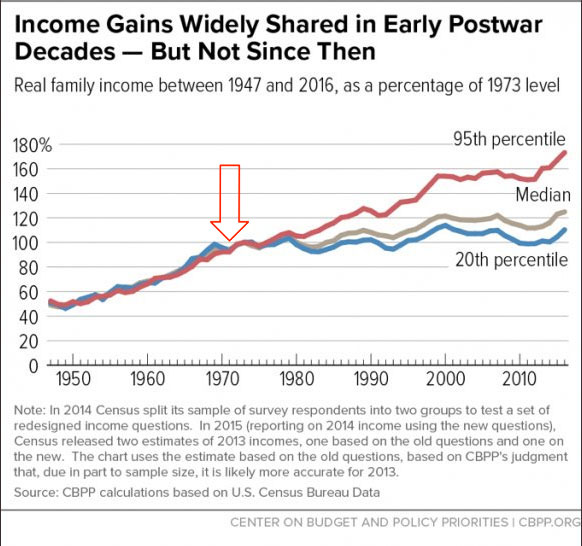

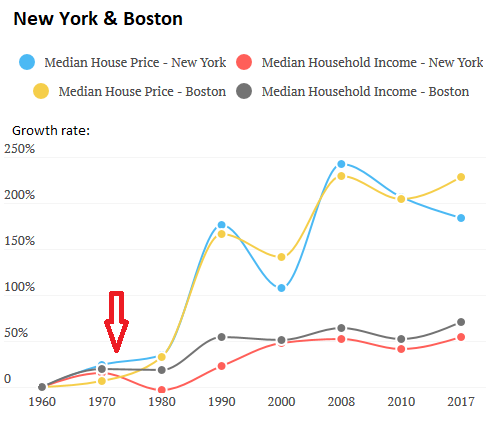

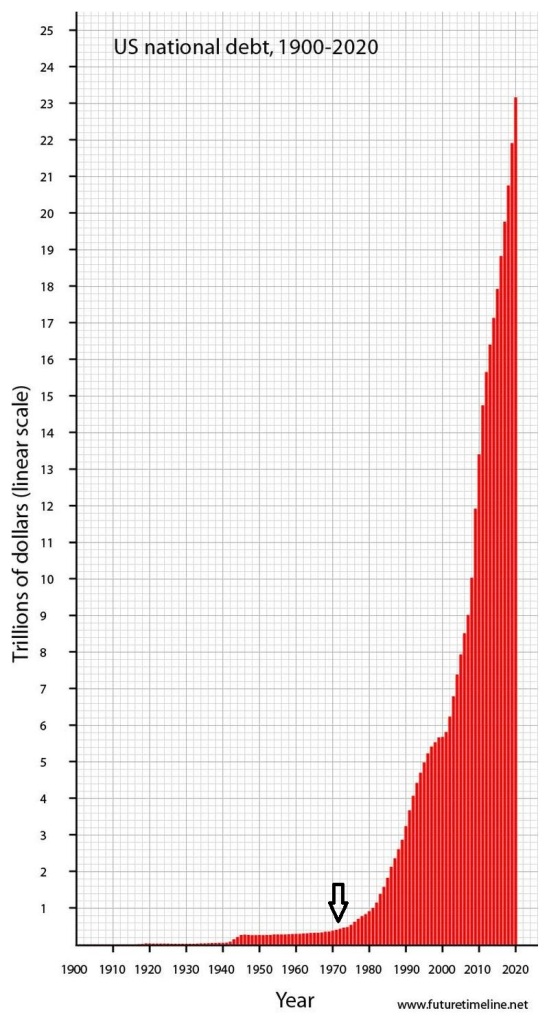

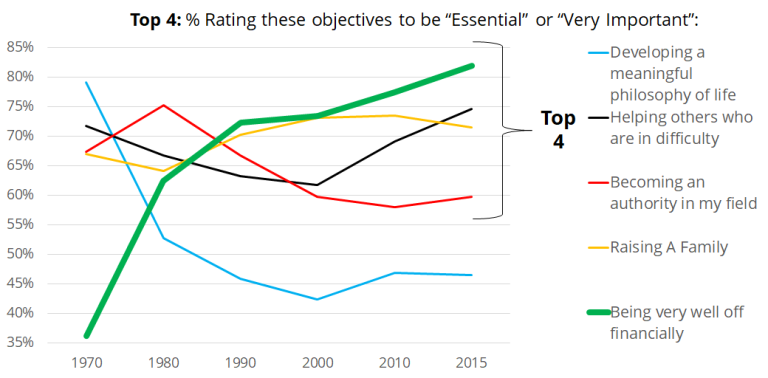

Let me just share a few graphs with you, courtesy of the aptly-named wtfhappenedin1971.com:

Alright, you probably get the point. The Federal Reserve was now able to make money printer go brrr every time the circumstance called for it. America was, at that time, also the industrial center of the free world and basically everybody was buying American products in exchange for American dollars. Because of its free-floating and now speculative nature, the value of the dollar skyrocketed and exchange rates to other currencies became incredibly favorable. In combination with the growing labor markets of countries outside of the West, it simply became far cheaper to outsource manufacturing and import products than pay American wages and prices in $USD - it should be no surprise that the millionaires became billionaires. The dollar was now the reserve currency of the Oil, in fact, is exclusively priced in dollars, AKA the "petrodollar" system. A guy you might have heard of by the name of Muammar Gaddafi tried to subvert this and directly trade oil for gold. Coincidentally, things did not end well for him. Nicolas Maduro announced in 2018 that Venezuela will trade oil for other currencies like the Euro and Yuan, in addition to launching a petroleum-backed cryptocurrency. Things are not going well there either. Saddam Hussein in 2000 also began trading oil for Euros and - well, you get the picture. Hey, put away that tin foil hat! , so the American economy shifted from tangible goods production to ethereal financial services. As described by Taken from Debt: The First 5,000 Years. A fantastic read in its own right, but the entirety of the last chapter explains this topic (and modern financial captitalism in general) far better than I possibly could. , "in a word - neoliberalism".

Regardless of whether you're an MMT economist and you think money printers are great, or you're a Ron Paul-style goldbug and any inflation whatsoever makes you froth at the mouth, or you don't really care and think Bitcoin is what everyone will be buying their morning coffee with in 50 years, this is the undeniable reality of the past half century of US monetary policy.

Gears and Levers

If you're an American zoomer like yours truly, you've probably grown up hearing things like, "One day China's gonna ask for all that national debt back!", or jokes about how everything in the supermarket has a MADE IN CHINA sticker. Turns out, people growing up in the 70s and 80s had near identical economic fears and a totem to represent them - although it wasn't China, but Japan. For the first time in the history of the nation, a good portion of your belongings could have been manufactured outside of the United States. You drove a Toyota or a Subaru to work, maybe rode a Honda motorcycle, watched the news on a Sony television, played video games on a Nintendo Entertainment System, and so on. Meanwhile, the industrial and economic heartland of the US was slowly decaying into what it's known as today - the Rust Belt. People were legitmately terrified that Japan was going to practically turn the United States into an emasculated client state within a few decades. Combined with lingering attitudes towards Japan from World War II, the idea that our cities would one day be lined with streetsigns and advertisements in Japanese was a collective nightmare of an enemy within the gates.

What little industry left in the country that couldn't be outsourced was starting to be overtaken by something totally new: automation. The Industrial Revolution of the previous century had augmented and multiplied the effectiveness of human labor; the wave of automation beginning in the 70s and 80s sought to totally replace it. Even the white collar workers of the time seemed no longer safe - the country was just about to enter the personal computing revolution, and operating systems like Unix were well on their way to revolutionize the information economy. Miraculously intelligent AI (or so it certainly must have seemed) in the form of expert systems were starting to appear and threatened to supplant human experts. We know now through the gift of hindsight that all of these systems were actually quite primitive, and even in the 21st century we're a long way from a totally autonomous economy. At the time, however, this was another serious economic anxiety for many people.

Alleyways

It is biologically impossible for the American boomer (Americanus boomericus) to speak for longer than ten minutes without mentioning just how great things were back in the good ol' days. This is especially true when it comes to crime - somehow everyone over the age of 50 in the US grew up in a neighborhood where "nobody ever had to lock their doors." And then, when they fall for the media being the media and If you haven't seen Nightcrawler (2014), you should definitely give it a watch. Obviously it's fiction, but it's an excellent portrayal of some of the warped incentives involved with the media and how it reports crime to the public. alarming or frightening stories, they can't help but think that the world is circling the drain.

This narrative couldn't futher from the truth. This country, and most countries, have never been safer than they are today. Crime rates across the board in the 1970s were almost double what they are now. People love to point to this trend as justification for any number of things have that happened in the meantime like "tough on crime" policies, the War on Drugs, militarization of the police force, etc. Turns out, the only thing that correllates well with this reduction in violent crime is atmospheric lead content. Lead poisoning results in a significant drop in IQ and reduced impulse control, and we might as well have been taking lead bong rips via constantly inhaling leaded gasoline exhaust. No wonder crime rates magically dropped after we banned leaded gas.

It's hard to imagine the '70s as anything other than the "peace, love, and hippies" aesthetic, but take a quick look at any frank description of the period and it's a whole different story. I mean, this was a time when people were warned that if they walked into Central Park at night, they wouldn't be walking back out. Vigilante groups had to start patrolling the New York subway system just so ordinary people wouldn't be preyed upon on their way to work. You could simply murder people and get away with it to such a degree that the '70s were called the "Golden Age of Serial Killers".

Crime, much like labor, was also getting a new chromium finish. Phone phreaking had already entered its zenith by the early 1970s, with some of the most influential figures in technology like Steve Jobs, Wozniak, and Bill Gates getting their start there. Serious cybercrime as we know it today was still in chrysalis, but the hacker subculture that influenced it (for better or worse) was beginning to take shape. The sacred text of hacker culture, the Jargon File, was posted in '75; the closest thing to a hacker flag, the Glider, was also popularized in the '70s.

Synthesis

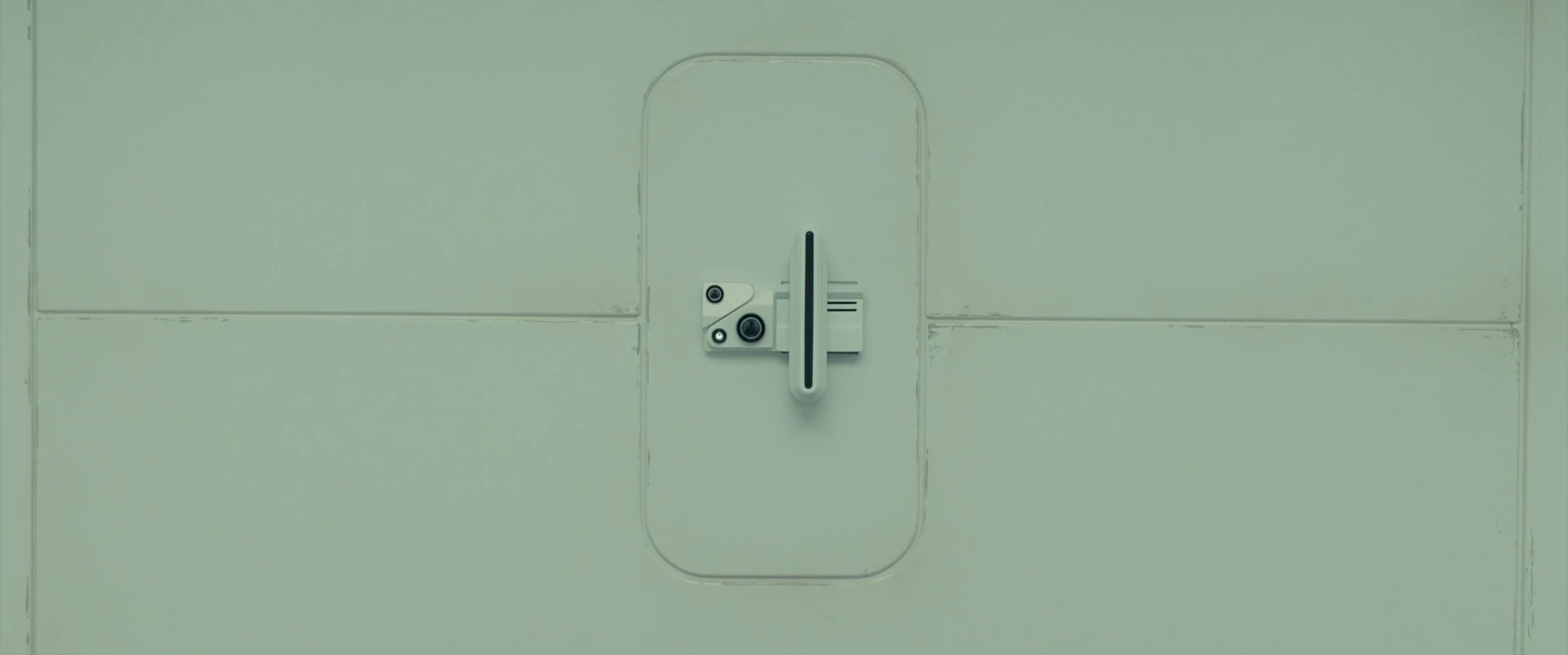

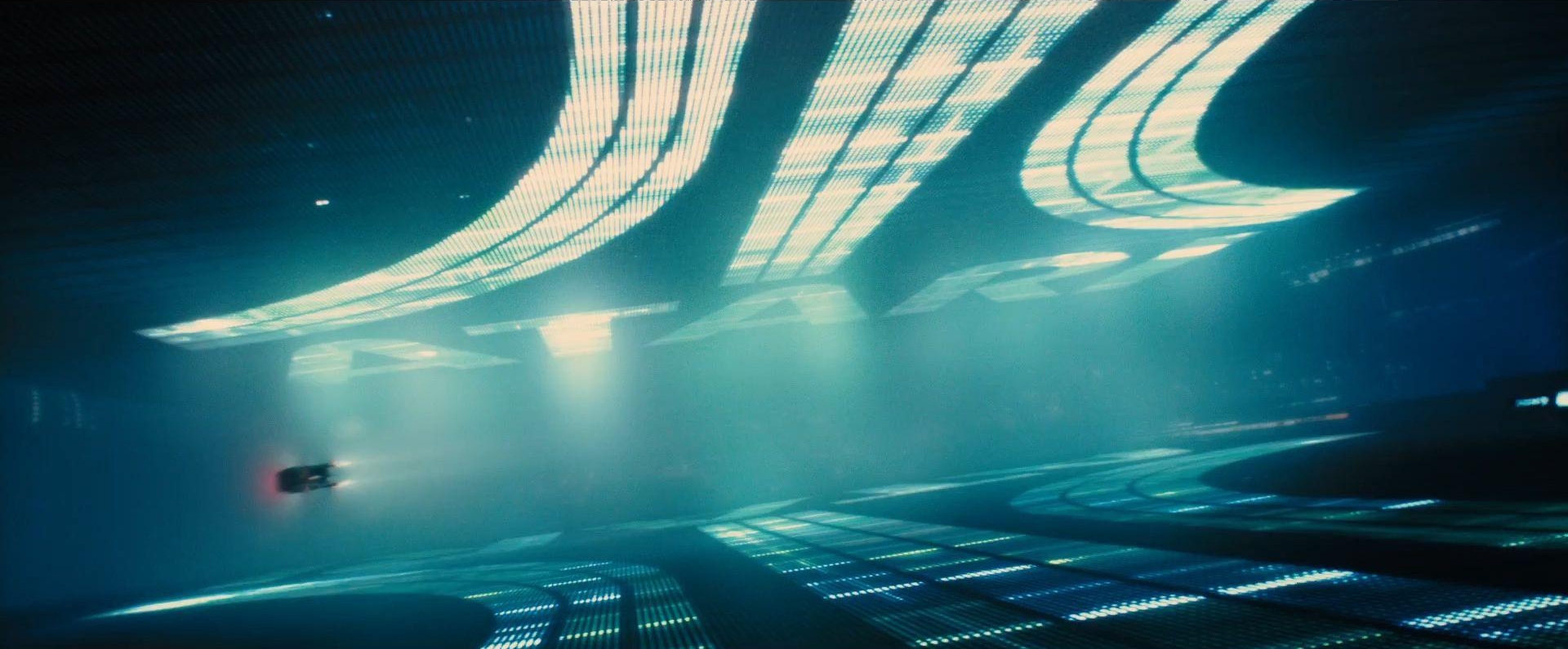

All the ingredients of cyberpunk soup - runaway crime, environmental decay, advanced technology mainly benefitting the rich, unless cleverly abused by the poor, anxieties of foreign influence - can be traced to the early '70s in the United States, and (more often than not) even more specifically to a single quirk of monetary policy. As mentioned previously, cyberpunk is also surprisingly adaptive. Although some of the more immediate perils of its original era may have changed shape, the media reflects them nonetheless. One of my favorite movies, Blade Runner 2049 (which all the images on this post are taken from), is probably the most clear example of this.

The original Blade Runner, as a cyberpunk classic, portrayed gargantuan neon Japanese signs lining the Los Angeles of near-future 2019. As explained previously, this was inspired by contemporary fears surrounding Japan as a rising economic power. Blade Runner 2049, released in 2017, didn't have the same social and economic context. In the real world, Japan has been in economic recession or stagnation for most of the past 30 years. In 2049 there are obviously the huge neon Japanese signs serving as a callback to the original film, but if you pay attention to the background of some scenes you can see snippets of text on signs or logos written in Hindi and Cyrillic script. This is pretty clearly a nod towards some of the worries endemic to the US about the shifting world around us; as someone working in tech in the 21st century I constantly hear (in my opinion misplaced, and sometimes outright xenophobic) worries that the industry is undergoing a crisis of outsourcing to India, and it also seems like every other day now I read a Hacker News post about some terrifying new cyberattack rumored to be perpetrated by Russian state-sponsored hackers. Another set piece of the movie that really struck me was the sea wall surrounding the city of Los Angeles. Ocean levels in 2049 had risen to such a degree that most of LA is actually below sea level, with waves crashing against the bulwark at perilous altitudes higher than the tops of skycrapers. In the '70s, toxic smog seemed the most pressing environmental issue. Now, we worry that the ocean itself will rise up and swallow us.

As much as I love Blade Runner 2049, the movie is ultimately an artifact of a bygone era. Cyberpunk as a kind of cautionary tale seems to no longer have any kind of weight to it, and more modern derivations are just self-indulgent rather than warnings against things to come (Cyberpunk 2077 was created by legions of overworked and underpaid game devs, after all). The younger generations have either consigned themselves to the existence of all the troubles that inspired cyberpunk, or they have simply known nothing else nor could even imagine anything else.

It'll be interesting to see what fiction inspired by the existential fears of the 21st century will look like. The closest thing I can think of is the Netflix series Black Mirror, but I always get the feeling that it's constrained by the traditional TV format and only ever scratches the surface. Interactive media like video games have been incredibly refined since the turn of the millenium, and technologies like VR have enabled entirely new experiences. Metal Gear Solid 2 is a good commentary on mass media and postmodernism that's aged very well, but it still predates the enormous and ever-important context of social media and a waning physical/digital divide.

A small but growing part of me has a feeling that the kind of hyperaccelerated media consumption enabled by the Internet and social media will ensure that today's "aesthetic of the future, as dreamt by the present" never comes to fruition. Why bother with fleshing out a screenplay, when you can mainline dopamine via a half-baked viral tweet? Conversely, I have friends my age who are literally incapable of sitting through a two-hour movie without concurrently consuming digital entertainment or getting bored and turning it off entirely. This isn't an indictment of "kids these days" (I'm one of them, after all), but rather a reflection of the standard of media now - like all things cyberpunk: accelerated, cheapened, and decayed.

All those stories yet to come now lost, like tears in rain.